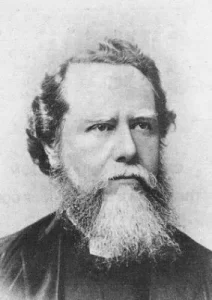

James Hudson Taylor

1832-1905

English Missionary to China

Quotes:

God’s work, done God’s way, will not lack God’s supply.

Christ is either Lord of all, or He is not Lord at all.

We are not only to renounce evil, but to manifest the truth. We tell people the world is vain; let our lives manifest that it is so. We tell them that our home is above and that all these things are transitory. Does our dwelling look like it? Oh to live consistent lives!

Biography

Hudson Taylor was the most widely used missionary in China’s history. During his 51 years of service there, his China Inland Mission established 20 mission stations, brought 849 missionaries to the field (968 by 1911), trained some 700 Chinese workers, raised four million dollars by faith (following Mueller’s example), and developed a witnessing Chinese church of 125,000. It has been said at least 35,000 were his own converts and that he baptized some 50,000. His gift for inspiring people to give themselves and their possessions to Christ was amazing.

Taylor was born into a Christian home. His father was a chemist and a local Methodist preacher who himself was fascinated by China in his youth. Once at age 4, Hudson piped up, “When I am a man I mean to be a missionary and go to China.” Father’s faith and mother’s prayers meant much.

Before he was born they had prayed about him going to China someday. However, soon young Taylor became a skeptical and worldly young man. He decided to live for this life only. At 15 he entered a local bank and worked as a junior clerk where, being well adjusted and happy, he was a popular teen. Worldly friends helped him scoff and swear. The gaslight and the murk of this winter left his eyes weak the rest of his life. He left the bank in 1848 to work in his father’s shop.

His conversion is an amazing story. When he was 17 years of age he went into his father’s library one afternoon in June, 1849 in search of a book to read. This was in a barn or warehouse adjacent to the house. Finally he picked up a gospel tract entitled, “It is Finished,” and decided to read the story on the front. He came upon the expression, “The Finished work of Christ,”

Remembering the words, “It is Finished,” he raised the question — “What was finished?” The answers seemed to fall in place and he received Christ as his Saviour. The same afternoon and time, his mother was visiting some 75 miles away. Experiencing an intense yearning for the conversion of her son, she turned the key in the door and resolved not to leave the spot until her prayers were answered. Hours later she left with assurance. She returned 10 days later and was met at the door by her son who said he had good news for her. She said, “I know, my boy. I have been rejoicing for a fortnight in the glad tidings you have to tell me.” Mother Taylor had learned of the incident from no human source, but God had assured her.

Months later he began to feel a great dissatisfaction with his spiritual state. His “first love” and his zeal for souls had grown cold. On Dec. 2, 1849 he retired to be alone with the Lord and it seemed this was the time to promise the Lord he would go to China. Hudson started to prepare immediately by exercising in the open air and exchanging his feather bed for a hard mattress. He distributed tracts and held cottage meetings. With the aid of a copy of Luke’s Gospel in the Mandarin dialect, he studied the Chinese language. He borrowed a book on China from a Congregational minister and began the study of Greek, Hebrew, and Latin.

In November, 1851, Hudson moved his lodging to a noisy suburb of Darinside, a neighborhood on the edge of town. Here he began a rigorous regime of saving and self-denial, spending spare time as a self-appointed medical missionary in cheerless streets where low wages, ever large families and gin produced brutalized husbands and wives and sickly children.

Here he set up a test situation regarding his salary. His employer had asked Hudson to remind him when his salary became due. Taylor did not do this. One day in a poor home with evidently starving children, he prayed for them but had no peace until he gave the family all he had even down to his last coin. He went home happy in heart and the next day the postman brought a letter with enough money to make a 400% profit for only a twelve hour investment. He was convinced that money given in Christ’s name was a loan which God would repay…and He did!

One night about 10 p.m. on the day his rent was due (and his pockets were empty), his employer came by with his back wages. Experiences like these prepared him for his future life of faith.

In the Fall of 1852, he came to London under the auspices of the Chinese Evangelization Society, who arranged to pay for his training as a doctor at the London Hospital in the East End.

Glowing reports came from China and the CES urged Taylor to leave at once, medical course unfinished, to reach the Taipings (new rebel group called Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace) at Nanking. These were supposedly Christian rebels that toppled Nanking in March, 1853. This Chinese rebellion lasted from 1850 to 1864.

After further medical studies in London, he accepted appointment under the CES and sailed from Liverpool on September 19, 1853. He was the only passenger in the sailing vessel, Dumfries. He had a tempestuous voyage as the ship on two occasions was within a few feet of being wrecked. One harrowing experience is worth remembering. The sailing vessel was becalmed in the vicinity of New Guinea. The captain dispaired as a four knot current carried them swiftly toward sunken reefs near shore. “Our fate is sealed!”

Cannibals were eagerly awaiting with delight and fires burning ready. Taylor and three others retired to pray and the Lord immediately sent a strong breeze that sent them on their way. Again one of his favorite texts, John 14:13 was proven. He finally reached Shanghai, China, March 1, 1854.

China at last…age 21 years, 10 months old! He was not prepared for the civil war on his doorstep. It was a shock to find that if the rebels did embrace Christianity, it was nominally on the part of the leaders alone from political motives. “Of the spirit of Christianity they knew little and manifested none.” He was forlorn, miserable and homesick. His eyes were inflamed, he suffered headaches and was simply cold in the climate.

His leisure time was consumed with long letters home to parents and sister. 1854 was still uncertain. As the military situation allowed, he explored the countryside, pursuing a hobby of insect and plant collecting, plus photography. Other missionaries took him on preaching tours and the Imperial Fleet once nearly opened fire on their boats at night in Woosung Creek. He was the only missionary actually a resident in Shanghai and this renewed his zeal for souls. But physical set backs and the possible civil war coming ever closer made him realize life was no longer safe.

He soon evacuated to the International Settlement geared for the foreign population. He was appalled at the idleness of many missionaries and their critical, sarcastic remarks. In early 1855 he started preaching tours — a week or more with another missionary or alone. There were ten such journeys his first two years. In February, 1855, the Imperial armies with rebel French support had stormed and sacked the starving city of Shanghai, making the streets hideous with human suffering. As peace returned he considered permanent residence in some interior city, or else he must find his way 700 miles to Nanking, capital of the Taipings. Either would forfeit consular protection. Before deciding, he went up the Yangtze River for three weeks in April with John Burdon. It was a trip that nearly cost their lives. At Tungchow, a city of evil repute, they were attacked by ruffians and were brought to a magistrate of sorts who saw that they were escorted safely out of the city.

Back at Shanghai, Taylor decided to reach the Taipings. Ten days later he was off. Partly to explore openings for future residence and partly to throw Imperialists off his trail, he proceeded up the Yangtze leisurely. From his boat, he visited 58 villages. Only seven of them had ever seen a Protestant missionary. He preached, removed tumors and distributed books.

The people would run from him at times or throw mud and stones. Medical box and skill was the only thing used to combat this. Passing his 23rd birthday he came within 70 miles of the Taipings. However he was divinely hindered in his attempt to reach Nanking, and in five more years the rebels were all but extinguished anyway. Taylor returned to Shanghai and on August 24, 1855, he toured southward to Ningpo. Now he was writing a girl back home, Elizabeth Sisson, proposing marriage…not even noticing young Maria Dyer who lived there (whom he eventually did marry).

On October 18, 1855 he left Shanghai again, this time going to Tsungming, a large island in the Yangtze mouth. He felt this would be a good place to labor and on November 5 he returned to Shanghai to restock the medicine chest, collect letters and fit himself with winter clothes. However he was then ordered out of Tsungming permanently, as local doctors complained to the magistrate that they were losing business to the foreign doctor. These six weeks were his first “inland” experience.

William Burns, a Scottish evangelist, came across his path and for seven months, 1855-56, they worked together as a gospel team. In February of 1856, they both felt called to Swatown, 1,000 miles south. They decided to go and arrived March 12. It was no easy place to get the attention of a hardened embittered people.

Tropical summer soon put Taylor into a state of exhaustion as the prickly heat and unending perspiration plus the stench of the night soil pails left him weak. He left his rice diet in May and added tea, eggs and toast. The mail was not encouraging either. Miss Sisson rejected his proposal to join him, and the CES, his mission board, informed him there were no funds left to send to him.

By midsummer, 1856, he was torn 100 different ways, but in July he decided to go back north, at Burns request, to get much needed medical equipment from Shanghai. Taylor arrived to find nearly all his medical supplies had been accidentally destroyed by fire. Then came the distressing news that Burns was arrested by Chinese authorities and sent on a 31 day journey to Canton.

Hudson then decided to settle at Ningpo and in October, 1856, made his way back there. On his way down he was robbed of his traveling bed, spare clothes, two watches, surgical instruments, concertina, sister Amelia’s photo and a Bible given to him by his mother. With no salary coming in now he would have been destitute and helpless had not his expenses fallen sharply because he had adopted the Chinese dress and level of living. Despite his setbacks he continued to preach to those who were in darkness.

As 1856 ended and the new year began, he knew he would have to resign from his mission board, CES. He considered joining some other society but a letter from George Mueller encouraged him to live by faith. So in June he resigned at age 25.

Dr. Parker, a fellow missionary, had established a hospital and dispensary at Ningpo. A new family, the Jones’, had arrived and the missionary community was fervent in spirit. Once a week they all dined at the school run by Miss Mary Ann Aldersey, a 60 year old Englishwoman, reputed to be the first woman missionary to China. She had two young helpers, Burella and Maria Dyer. Burella became engaged to missionary associate, John Burdon.

On Christmas day, 1856, the missionary compound had a party where a friendship between Hudson and Maria developed. Taylor had to return to Shanghai, but on March 23 he wrote asking to be engaged. Ordered by Miss Aldersey (a guardian of sorts), Maria painfully refused. However, as both plunged into the Lord’s work and prayed, they decided to get engaged on November 14, 1857, approval or not.

As 1859 came around, Maria turned 21 (born January 16, 1837), and four days later on the 20th, she married Hudson Taylor. A happier couple could not be found…they had waited over two years.

The work in the compound continued. John Jones became the pastor, Maria ran the little school as Taylor’s small group at Ningpo kept pursuing mission work in a great heathen city. In 1859, Mrs. Taylor fell grievously ill, recovering to give birth to their first child, Grace, on July 31.

The treaty of Tientsin, ratified in 1860, gave missionaries new freedoms but Taylor’s health was so bad with all the pressures that a furlough seemed to be his only hope for life. So in August they left Shanghai, arriving back in England in November, 1860, seven years after he first left for China.

They lived in Bayswater where their first son, Herbert, was born (2nd child) in April, 1861. Taylor, realizing he could not soon return, undertook various responsibilities. First, the translating and revision of the Ningpo New Testament (a five year project) and then enrolling in a medical course. He also wrote a book, China, It’s Spiritual Needs and Claims (October, 1865). Other children were born. Bertie (number 3) came in 1862, followed by Freddie in 1863 and Samuel in 1864. As only four children returned to China, it is thought that Herbert must have died in infancy. These London years brought tests as severe as any that followed with poor health, funds and a growing family.

The China Inland Mission was born on Sunday, June 25, 1865 on the sands of Brington’s beach where Hudson Taylor was gripped with a heavy burden and asked God for 24 missionaries to return with him to China. He opened a bank account with $50.00 and soon the volunteers and money began coming in. At this time Spurgeon heard Taylor and was impressed by his zeal for China. Apparently God was too, for within the year, he had raised $13,000.00 and accepted 24 volunteers. On December 7, a baby born prematurely died at birth. Maria’s lungs were permanently affected with tuberculosis at about this time and it took months for her to recover.

On May 26, 1866, the Taylors left for China after 5½ years of working and recruiting at home. Of the 24 volunteers, eight preceded him and 16 came with the family. On board were a married couple, five single men and nine single ladies. They ran into a terrible typhoon in the South China Sea and only prayer and work beyond measure aboard the Lammermuir prevented a catastrophe.

On September 30, 1866, they were towed towards Shanghai by a steam tug. It was back to Ningpo by canal, but over crowded conditions at the missionary compound compelled him to go to Hangchow in December. Taylor’s methods were met with scorn, the Chinese dress being the big item that annoyed the western community as it did previously. Keeping his new missionaries in line with his policies was somewhat a task also. In early February, 1867, little Maria was born (number 6). By April the group was in danger of a split. Taylor admitted his folly in rebaptizing Anglicans and never again swerved from a true interdenominational position.

He went westward in June looking for new stations. The heat climbed to 103 degrees in August. Taylor was recovering from inflamed eyes and wife Maria was ill. The death of 8 year old Gracie Taylor on August 23, 1867 probably saved the mission. The girl was praying for an idol maker just before she died and it united the mission. In September, 1868 the last dissident was dismissed.

The Taylors had gone to Yangchow on June 1, 1868 with their four children. By July 20 they had their own compound. Suddenly handbills warned against the foreigners. Ignorance and priestly hostility brought fear of the West. Not only that, but the foreigners (Taylors) offered exceptional prospects for looting.

Saturday, August 22, 1868 has to be one of the most traumatic days in the mission’s history. The mission compound was attacked and as Taylor and a friend ran for help, the home was looted and burned causing serious injuries on several individuals. The battered missionaries left Yangchow for Chinkiang where they were made comfortable. Maria Taylor could not walk unaided and ached in every bone. However, they did not want to press charges. The British Navy, hearing of the problem, sailed up the Yangtze deep into the territory to protest this outrage. This was to produce negative results as Western Imperialism became the excuse for Communist infiltration later.

The Taylors returned to Yangchow on November 18, 1868. Charles Edward was born November 28 (number 7).

Although Europeans in Shanghai appreciated the problem in Yangchow, back in England the stories were perverted and the Taylors sneered at. In Yangchow the natives were impressed that the Taylors would come back and the next year saw a time of reaping. In England, George Mueller refused to believe the libel and his contributions ($10,000 annually) made up for the support that stopped.

Exhausted and depressed, Hudson later confessed that only his wife’s love stood between him and suicide. At this point in his life God used the situation to do a new thing. Hudson Taylor could not go on as he was bankrupt in spirit and strength. It finally dawned on him reading a missionary friend’s letter. “I have striven in vain to abide in Him, I’ll strive no more. For has not He promised to abide with me…never to leave me, never to fail me?” He then entered into what he thereafter called the “Exchanged Life” where his work for the Lord was no longer done in his own strength.

In 1870 a most heart rendering decision had to be made. The children (older four), ages 9,7,5 and 3 should go back to England, leaving only baby Charles with the parents. Fear of parting was too much for Sammy. He died on a boat on the Yangtze River on February 4, 1870. On March 22 at Shanghai, the parents wept as they said farewell to Bertie, Freddie and little Maria who would go home with missionary Emily Blatchley who would act as their foster-mother.

Little did Mrs. Taylor know how wise a decision this would be for she herself would be dead four months later. On June 21, a massacre of many foreigners in Tientsin made things tense again. But is was Maria’s tuberculosis condition worsening under the extremely hot sun that caused the greatest concern. On July 7, little Noel (number 8) was born. he lived for 13 days as throat problems in the oppressive heat were just too much for him. Four children were now in heaven as July 20th added another. Three days later the brave Maria died on Saturday, July 23, 1870. She just got weaker and weaker and passed on peacefully. Official conclusion was prostration by cholera.

She was 33 and during their 12 years of marriage gave birth to eight children plus one stillborn. She was a tower of strength to her husband. Certainly, along with Ann Judson, Maria Taylor was one of the most heroic wives in Christian history. Two days before she died they received word that the other children had arrived safely in England. She was buried at Chinkiang.

Taylor himself had a breakdown in 1871. A badly deranged liver made him sleepless leading to painful depression of spirit, and difficulty in breathing. At the same time, the Bergers back in England could no longer care for the home side of the Mission because of failing health and he was retiring in March 1872. Hence Taylor had to return to England to care for this need as well as his health.

He returned home in July, 1871 where a Miss Faulding came into his life. He married her in London later that year. He also formed the London Council of the CIM on August 6, 1872, and at a Bible Conference that year, young Dwight Moody heard him preach. he returned to China on October 9, 1872 bidding farewell to his beloved children and taking his new bride with him. Mission work continued. An interesting conversation on January 26, 1874 challenged him further.

In April, 1874 he wrote a friend, “We have $.87 and all the promises of God.” In June came a letter from an unknown friend in England with $4,000 marked for extension of his work into new, untouched provinces. Also, that month he opened the western branch of the Mission in Wuchang with Mr. Judd.

Now the emergency was back in England as the foster-mother Miss Blatchley died July 26, 1874. Again the Taylors hurried home, and on the way up the Yangtze a fall seriously injured Mr. Taylor. General paralysis of the limbs confined him to the couch. He could only later turn in bed with the help of a rope fixed above him. Health finally came back after the long 1874-75 winter. Mrs. Taylor had to stay in England to care for her own two children recently born (including Howard, the biographer and author of his father’s life story), plus the four from the previous marriage and an adopted daughter.

In January 1875 Taylor appealed in prayer for 18 pioneers for the nine unevangelized provinces. On September 13, 1876 a political settlement was reached between England and China with the signing of the Chefoo Convention which opened inland China to the gospel. Hudson, himself went back to China where he was to travel 30,000 miles the next two years (1876-78) opening new stations. His journey kept him on the road months at a time in widespread evangelistic journeys inland. In hours of trial and loneliness he would play his harmonium and sing some of the great Christian hymns — his favorite being, “Jesus, I am resting, resting, in the joy of what thou art.”

In 1878 his wife was able to rejoin him on the mission field. She led in the advance of women’s missionary activity into the far interior in the fall of 1878. The following fall, Mrs. Nicoll and Mrs. Clark pioneered the way for women’s work in western China. The first woman missionary allowed to go into the interior on a resident status was Emily King who died in May of 1881 at Hanchung. There were now about 100 missionaries in the organization and they decided to pray in November 1881 at Wuchang for another seventy to come out in 1882-84.

Taylor sailed home in February, 1883 and was powerfully used by the Lord. At the end of the year he had 70 new workers sailing for China and $14,000 raised. These included the Cambridge University seven that sailed on February 5, 1885. Taylor returned to China rejoicing in the developments. They now had 225 missionaries, 59 churches and 1,655 members. Taylor decided that to open China up from end to end would take 100 new workers, so London was cabled, — “Praying for 100 new workers in 1887.” This was the first meeting of the China Council held in Anking. Taylor went back to England to challenge recruits to join him. Actually 600 offered to go, but Taylor screened and chose 102. He prayed for $50,000 and raised $105,000. At the years end all 102 had joined the staff on the field. More than $22,000 was raised to pay their passages.

Taylor was about to return when urgent invitations from Henry Frost came to visit America in December. He decided to go and on his only trip to America he preached at Moody’s Northfield Conference and a few other places making a profound impression. As he went back to China in the Fall of 1888, he was able to take 14 candidates along from America.

Taylor had to return to England because of ill health and was semi-retired in Switzerland as a result. He was brought to the very doors of death by the terrible news of the Boxer Rebellion, the resulting disruption of the work and murder of hundreds of missionaries along with the native Christians. It was May, 1900, and as the telegrams came telling of riots and massacres, he gasped, “I cannot read, I cannot pray, I can scarcely think…but I can trust.” Although the anguish of heart nearly killed him, the stories coming out of the holocaust actually inspired great interest in missions everywhere and gave new life to the CIM. D.E. Hoste was appointed Acting General Director in August, 1900. In November, 1902, Taylor resigned to turn the reigns over to younger men.

Not knowing he had only three months to live, he left for China one last time…his 11th trip there, leaving in February, 1905, and arriving in March. He went alone as his beloved wife had passed on in Switzerland on July 30, 1904.

He spent Easter at Yangchow where 32 years before, his house was burnt to the ground. Then to Chinkiang where he buried his first wife 35 years previously. Then on to Honan, Hankow, and finally to Changsha, the capital of Hunan. This was the most difficult of the nine unevangelized provinces entered by his workers.

Here he visited various parts of the city, inspected a site for a new hospital, spoke to a congregation of Chinese Christians, attending a reception given in his honor in a garden, and was planning to speak on Sunday. But he died quite suddenly on Saturday evening. He had retired to his home, his daughter-in-law, Mary (Mrs. Howard Taylor) visited him as he was busy going over his homeland letters. One gasp and he was gone. Christians carried his body to Chinkiang where he was buried with his Maria at the foot of green hills near the Yangtze River.

The above is one of 46 booklets by Ed Reese in the Christian Hall of Fame series. These short biographies provide good material for Sunday School lessons, family devotions, and reading for young people and adults. Order/information from: Reese Publications

You can use PayPal to make a donation or send a check in the mail. One time donations help temporarily but we need friends who will commit to giving regularly. Would you prayerfully consider doing so?

You can contact us if you have a prayer request or if you have any questions.