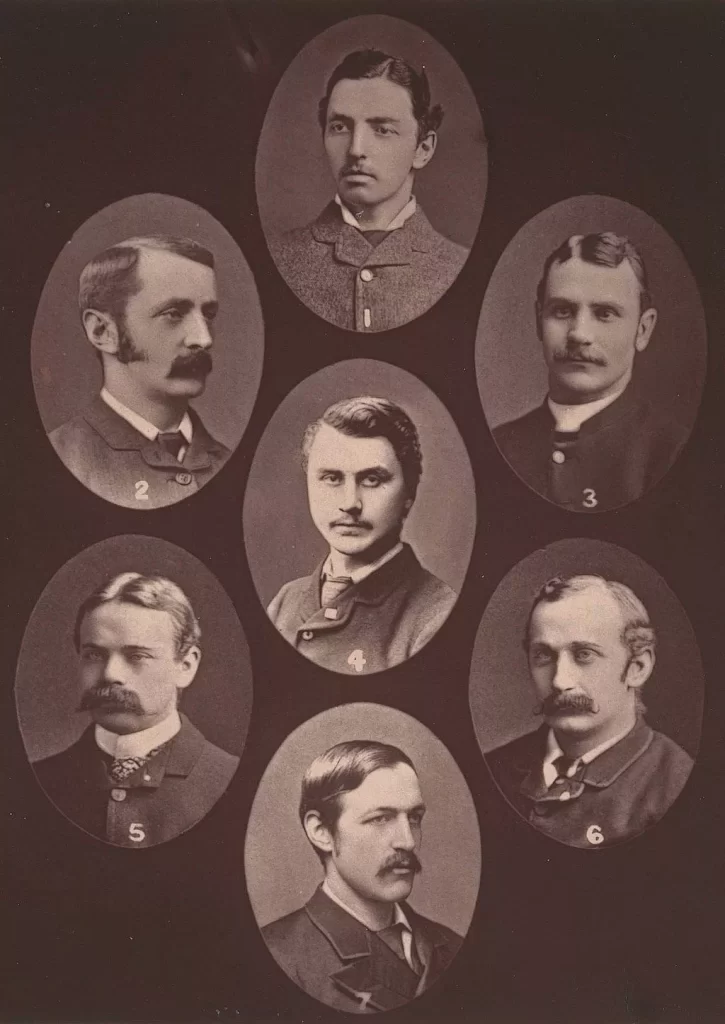

Cambridge Seven

C. T. Studd, M. Beauchamp, S. P. Smith, A. T. Podhill-Turner, D. E. Hoste, C. H. Polhill-Turner, W. W. Cassels

And He said unto them, Go ye into all the world, and preach the gospel to every creature.

Mark 16:15

Biography

The seven young men who came to be known as “The Cambridge Seven” were all Englishmen, but the story of how God used this handful of students really begins in China, with a medical missionary named Dr. Harold Schofield. Dr. Schofield was a member of the China Inland Mission, the first Protestant mission allowed to penetrate into the interior of China and it was the mission pioneered by Hudson Taylor in 1866. Dr. Schofield had been a brilliant young doctor at Oxford who gave his life to Jesus and at the age of 29, God sent him to China as a missionary.

There was nothing glamorous about missionary life in the interior of China. The stench of dung, mingled with the stench of unwashed bodies was everywhere. Disease was common, especially among the poor, peasant class, and in fact, Dr. Schofield would later die from typhus, contracted in his mission field.

At the time, few in England were interested in China mission. Fewer still had even heard of Hudson Taylor’s China Inland Mission and the handful who did go to China were not university men, “trained in mind and body for leadership.” Students in the universities were not interested in foreign missions and actually, there were not many students who were deeply interested in Jesus. Of the university students who had answered God’s call to be missionaries, they wanted to follow the paths blazed by Dr. David Livingstone in Africa or the footsteps of William Carey in India.

As Dr. Schofield surveyed the province (Shansi) in which he lived, with its nine million unsaved heathen Chinese and only five or six missionaries total, combined with the sleeping church back in England, he should have packed up his bags and went home in utter defeat. However, Dr. Schofield was a man of prayer and so night after night, “leaving behind food and leisure,” he got on his knees and prayed that God would raise up Bible teachers and shepherds, especially from the universities and send them to China as missionaries.

When Dr. Schofield died, he did not physically see much answer to his prayer. But God was working in such a way as not only to answer one man’s faith and prayer but to awaken an entire nation from its spiritual slumber.

First, consecration and dedication of seven young men.

In 1873, Dwight L. Moody and his co-worker, Ira Sankey, began a three year evangelical mission of the British Isles. He was already a famous and respected evangelist in the United States but when he went to England, he was, at first, looked upon as a curiosity and the press especially did not like them. Many people ridiculed Moody, who did not speak well and Sankey, who was, at best, only an average musician. But strangely, many people went to their meetings, with the meeting halls often overflowing with people.

One of these attendants was a thirteen year old boy named Stanley P. Smith. He came from a Christian family and his father was a successful London surgeon. When Stanley Smith listened to Moody’s message, the Holy Spirit opened Smith’s heart to see his own sins and to see how Jesus “Christ had died on the cross, the just for the unjust, that he might bring us to God.” In Stanley Smith’s own words, “I was by grace enabled to receive Christ.”

We cannot deny the reality of Smith’s conversion and the power of the Holy Spirit. Two years later, as a student at Repton, one of the premier prep. schools in England, Smith joined a prayer meeting/Bible study formed by his friend Granville Waldegrave. But he was young, only fifteen years old, and he was often sick so his faith depended on how he was feeling.

His diary is full of entries of his own un-Christ like behavior. He wanted to become an Anglican minister but his faith soon degenerated into habit. Outwardly, he looked okay. He was popular and seemed happy. He worked hard at school and devoted his time to playing sports, even though he was often in pain. Smith was known for his good sense of humor. But he knew that he was not right with God. By 1880, the same life he had given to God when he accepted Jesus six years previous, Smith had taken it all back for himself.

In 1879, Stanley Smith entered Cambridge University (University of Cambridge). Rowing was Smith’s passion and in spite of his health, he joined the Cambridge rowing team and was placed in the lowest boat. His best friend from prep school, Montague Beauchamp, a tall, athletic type, was also a Cambridge student and member of the rowing team and the two were inseparable. Beauchamp also came from a Christian family, and his parents and uncle had been original sponsors of Hudson Taylor’s China Inland Mission.

Together, Smith and Beauchamp occasionally attended the Daily Prayer Meeting, weekly Sunday meetings of the Inter-Collegiate Christian Union and even taught Sunday school. But the two of them had not yielded their lives to Christ and soon, rowing became more important to Smith than any relationship with God, even a nominal one.

In April 1880, Granville Waldegrave, Smith and Beauchamp met for chapel service and then breakfast. Waldegrave was also a Cambridge student and had been praying for his friend Stanley Smith, for three and a half years. God was working and the conversation soon changed to a deep, spiritual conversation. Beauchamp was not ready yet, but Smith was. Smith confessed his own sin that he no longer had any joy from his salvation and was hardly a Christian at all.

Waldegrave showed Smith that making small, token pledges to God were useless and that he had to give himself fully to God, even as God in Christ had wholly given himself for us. Only then can we know the joys and unsearchable riches of Jesus and the power of the Holy Spirit. When Smith gave his life to God that night, he was changed forever. Smith would later say, “I decided by God’s grace to live by and for Him.” God had raised the first member of “The Cambridge Seven.”

One of Smith’s good friends from the rowing team was William Hoste, a Christian. Hoste had a younger brother named Dixon Hoste, a disinterested, callous and quiet young man, who although only twenty-one years old, was already a commissioned officer in the British army (a gunner subaltern), right below the rank of captain. Dixon Hoste was living a life “entirely indifferent to the claims of God,” as he would later say. He had been raised in a Christian family but he himself had no spiritual desire. He felt that his life was in the army and in fact, he had a bright future in it.

During the Winter of 1882, Dixon was on leave and William, home for Christmas break, tried to persuade Dixon to attend a meeting of Moody, who was in the midst of his second great evangelical mission of Great Britain. For three nights, Dixon refused to attend. On the fourth night, William’s persistence triumphed and Dixon went to the meeting, in spite of himself.

When Dixon listened to God’s word, his heart was opened. He saw his own ugly sins. His pride crumbled. Dixon’s deep dissatisfaction with his life overwhelmed him and he saw how much his dissatisfaction contrasted with the joyful life of his brother who knew Jesus. Dixon had heard the same message too many times already, but this time, he had to repent and give his life to the Only One who could save him, Jesus Christ. But Dixon Hoste felt it too costly, giving up his easy-going desires, incurring the ridicule of worldly people and the bad effect this might have on his promising military career.

Dixon’s brother William prayed for him and the Holy Spirit worked so that on the last night of the mission, Dixon knelt down and gave his life to Jesus. Then peace and joy welled up in his soul, like he had never known before. At that moment, Dixon realized that there was nothing better than to know, adore and serve his Lord and Master Jesus Christ. When Dixon returned to his post, he became a faithful witness of Christ. But with each passing day, he grew more and more sure that God was calling him to leave his commission and go out as a missionary. In due time, God would answer his call.

Montague Beauchamp had been childhood friends with the Studd family and at Cambridge, Beauchamp introduced Stanley Smith to Kynaston Studd, a member of the Cambridge cricket team. In fact, Kynaston was a rather famous cricket player (as were his younger brothers) but he was first and foremost, a Christian and he had a strong sense of mission to serve others in Jesus.

One day in early February of 1881, Smith, Beauchamp and Studd were hanging pictures in Studd’s room when Beauchamp felt ill and left early for bed. When the pictures had all been hung, Smith and Studd prayed together for their friend, Monty Beauchamp, who was really only a nominal Christian even though he came from a missionary family. Afterwards, Studd suggested that they get together everyday to pray for Beauchamp and Smith wholeheartedly agreed. So each day, Smith and Studd met and prayed fifteen minutes for their friend to give his life to Jesus.

God accepted the prayer of these two friends and opened Beauchamp’s heart. In early October of 1881, Montague Beauchamp “yielded all to Christ” and the three friends rejoiced together. Beauchamp was changed so much so that everyone could see how much Christ had done for him. Interestingly, Beauchamp and his family were friends with Hudson Taylor and were very familiar with China Mission. Beauchamp, saved by grace and owing a debt of love to his two friends and especially to God, would become the instrument in guiding the direction of “The Cambridge Seven.”

William Cassels was an acquaintance of Smith’s from the rowing team. They were different personality wise. Smith was out going while Cassels was a gentle and quiet young man. Furthermore, Cassels was three years older than Stanley Smith. Cassels was a Christian and was studying to be a minister. Cassels was not distinguished in any way, but he was a faithful man, serving in a slum-parish and considering going to Africa as a missionary.

After Smith gave his life to Christ, suddenly Cassels and Smith became very close friends. They attended the same Bible study and prayer meeting and prayed together for campus students, especially for the boat club of which Smith was the captain and therefore, a man of great influence throughout the whole college. Later, Cassels would become an instrumental figure in the formation of “The Cambridge Seven.”

Cecil Polhill-Turner and his younger brother Arthur were classmates and friends of Kynaston Studd and his two younger brothers at Eton, another premier prep school in England. Both Cecil and Arthur were exceptional athletes, excelling at cricket and football. According to tradition, Cecil, as the second son, would enter the military and Arthur would become a minister. But neither brother had much spiritual desire, even though their nanny had prayed for them from the time they were babies and told them wonderful Bible stories throughout their childhood. At Eton, Cecil and Arthur respected the athletic prowess of the Studd brothers who conducted a Bible study but the Polhill-Turners were not interested. Arthur even thought it was indecent to openly talk about Jesus.

In October of 1882, Arthur Polhill-Turner entered his second year at Cambridge. D.L. Moody and Ira Sankey were to appear at Cambridge as part of their evangelical Mission and each undergraduate at the university received a personal invitation to the meeting, signed by Kynaston Studd. Arthur, like many of his friends, thought it was ridiculous that these uneducated Americans were coming to one of the world’s best universities to preach to them.

He went, curious to see what would happen. At the meeting, God’s word spoke to his heart and Arthur could not help going back again the next night. He went night after night and when Moody spoke on the Prodigal Son, Arthur’s pride and sin were exposed. He had planned on using his position as a minister to earn an easy and comfortable living but he realized how much this grieved God. Arthur realized God’s grace and love for him, sending His One and Only Son to die for his sins. He saw how God had been calling both him and his brother Cecil, first through his nanny, then his sister and now, through Moody’s preaching.

One word of God pierced Arthur’s heart and took away his fear. That one word was Isaiah 12:2, “Behold, God is my salvation; I will trust, and not be afraid: for the LORD JEHOVAH is my strength and my song; he also is become my salvation.” On the last night of the Mission, Arthur offered himself to Jesus, just as he was, and Jesus accepted him just as he was. Arthur Polhill-Turner never looked back.

Cecil Polhill-Turner, like Dixon Hoste, had also become a commissioned officer in the British army (subaltern). During the winter of 1882-83, Cecil was on leave and he went home. Arthur immediately began to talk to his older brother about his new faith in Jesus and forced Cecil to promise to read a verse or two from the Bible each morning. Arthur also took Cecil to Moody’s meetings in London and Cecil was impressed. But Cecil had his own ideas about Christianity, thinking that Christians were sad because they were always thinking about their sins.

Furthermore, he felt that he could not give up his promising military career, which he felt he would have to do if he accepted Christ. God was working though and by the winter of 1884, he was praying everyday, his thoughts were occupied with the word of God and Christ, who was calling him to repent and accept Jesus as his Lord and Savior. Finally, his year-long spiritual struggle ended in victory for Jesus. In Cecil’s own words, “I had yielded to and trusted in Jesus Christ as my Savior, Lord and Master.”

Kynaston Studd, a friend of Stanley Smith, Monty Beauchamp and the Polhill-Turner brothers, had two younger brothers himself, George and Charles Thomas or C.T. [Studd]. Their father, Edward Studd, had made a fortune in India and the Studd family lived in complete luxury. Edward Studd had become a Christian in 1877, when his friend, Mr. Vincent, took him to one of Moody’s meetings. After Edward Studd accepted Jesus, he devoted the remaining two years of his life to bring the Gospel to anybody and everybody. He opened his home for weekly Christian meetings and invited Christian speakers to speak and all of his friends and neighbors to listen. He took his servants to listen to Moody. He worked doubly hard to convert his three sons.

Charles Studd would later say of his father, “I was not altogether pleased with him. He used to come into my room at night and ask if I was converted. After a time I used to sham sleep when I saw the door open and in the day, I crept around to the other side of the house when I saw him coming.” Through one Godly man whom Edward Studd knew, Charles accepted Jesus as his Savior and the Bible meant everything to him, when he was only seventeen. But unlike his brother Kynaston, Charles’s zeal for Jesus would slowly fade with time.

Charles Studd liked playing sports and he had a particular passion for cricket, the most popular sport in England at the time. He was not athletically gifted but he worked hard at his sport and was determined to become the best cricket player. He spent hours in front of a mirror, perfecting his swing and refusing to smoke or even be in the same room with smokers for fear it would hurt his eyes. As he played and practiced and watched other players, his own game improved to the point where he had mastered every facet of cricket.

He became captain of the Eton cricket team and his popularity grew and grew. In 1879, Studd entered Trinity College of Cambridge University (University of Cambridge) and from there his name no longer remained only in cricket circles. Rather, C.T. Studd became a household name throughout Great Britain. By 1883 Charles Studd was the captain of the Cambridge cricket team and he was the idol of undergraduates and school boys and admired by elders. Studd had become the Michael Jordan of cricket. Studd was recognized as the greatest player to have ever played the game, and years later, he was still recognized as the greatest cricket player since.

Yet all the while, his faith in Jesus grew cold. At Eton, Studd and his brothers Kynaston and George, had formed a group Bible study. While at Cambridge, his older brother Kynaston still devoted his heart to serving Jesus but Charles and George were lukewarm. Charles went to the occasional Daily Prayer Meeting and identified himself as a Christian, which, combined with his talents and good nature, gave him a good reputation amongst his peers and throughout the university. But he was not living for Jesus. Studd would later say, “Instead of going and talking of the love of Christ I was selfish and kept the knowledge all to myself. The result was that gradually my love began to grow cold, and the love of the world came in.” In short, he was only a nominal Christian.

In November of 1883, Charles’ younger brother George was dying. Charles loved his brother dearly and he was stricken with grief. But God used this event to change his life. When Charles looked at his dying brother, who was also a popular cricket player in his own right, he could only conclude, “Now what is all the popularity of the world to George? What is all the fame and flattering? What is it worth to possess the riches of the world, when a man comes to face Eternity?”

As George lay dying, his only concern was for the Bible and for the only one who could save him, Jesus Christ. Charles’ concern became the same. Miraculously, God restored George’s health and at the first opportunity, Charles went to hear Moody. While listening to God’s word, Charles’s heart was opened. Cricket did not matter; only a relationship with his Savior and Lord Jesus mattered. Charles T. Studd said, “There the Lord met me again and restored to me the joy of His salvation. Still further, and what was better than all, He set me to work for Him, and I began to try and persuade my friends to read the Gospel, and to speak to them immediately about their souls.”

Charles gave himself to God and God accepted him. God set him to work and God would use C.T. Studd, in a way greater than the cricket player could have ever imagined.

Second, the power of Christian fellowship.

When these seven young men yielded their lives to Jesus, they didn’t runaway to a cave and become monks. They didn’t shut their mouths and become quietly self-righteous. Instead, they continued to struggle and grow in love for Jesus and for others. They made the most of their situations for the sake of telling others about their Lord and Savior Jesus Christ, even though their individual positions meant nothing to them because of the joy and meaning they had in Jesus.

Stanley Smith was the captain of the rowing team and his friend Montague Beauchamp was also a member and together, they formed a group Bible study for the rowing team and prayed for their teammates to all become Christians. Stanley Smith had wanted to go out as a missionary but God had given him Ezekiel 3:5, “For thou art not sent to a people of a strange speech and an hard language, but to the house of Israel” and so at every opportunity he witnessed to others about Jesus.

Dixon Hoste wanted to resign his commission and also become a missionary but at the urging of his parents, he stayed in the army and told everyone about his new faith in Christ.

William Cassels, with deep evangelical zeal, was pastoring a church located in the slums of South Lambeth.

Arthur Polhill-Turner, the seminary student, co-working with his sister, went around telling people about his experience with Jesus and at Cambridge, he engaged in Christian activities with zeal.

Cecil Polhill-Turner decided to do everything the best he could for Christ, like the Old Testament Joseph, so that while some soldiers wanted to ridicule his faith, they couldn’t because he was such a good soldier. Both Cecil and Arthur also worked together at a Children’s mission.

Charles Studd, of great cricket fame, had only one desire; to win souls for Christ. He took several of his teammates to hear Moody preach and they were converted. Studd joined the Moody Mission and spoke at the subsidiary meetings, along with his brother Kynaston.

These men were being used precisely where they were. But God had a greater plan for them and brought them all together for one common goal. Monty Beauchamp became a seminary student and was good friends with Arthur Polhill-Turner, who, through Beauchamp, was the first to hear God’s call for China. In 1883, Stanley Smith was invited to speak at the seminary and there he met Arthur Polhill-Turner for the first time. It was also during this time that Smith received one word of God, Isaiah 49:6, “…I will also give thee for a light to the Gentiles, that thou mayest be my salvation unto the end of the earth.” Smith now had no doubt that God was going to send him out somewhere as a missionary.

Dixon Hoste was the second to hear God’s call to go to China. Through his brother William and probably Montague Beauchamp, Dixon had received a booklet written by Hudson Taylor called, “China’s Spiritual Need and Claims.” The contents was very simple. There were 385 million Chinese in the interior of China who were living in complete darkness. At the same time, Jesus commanded in Mark 16:15, “Go ye into all the world, and preach the gospel to every creature.” Dixon was overwhelmed with the spiritual need of the Chinese people and resolved to see Hudson Taylor who had just returned from China, to apply through the China Inland Mission to go as a missionary.

The Christian Union, of which Beauchamp and Arthur Polhill-Turner were members, had long been interested in Hudson Taylor’s China Inland Mission. Stanley Smith, through the good influence of Beauchamp, also became interested in China and after much prayer and personal talks with Hudson Taylor, applied in January of 1884 to go as a missionary through the C.I.M. Smith also went to see his good friend, William Cassels, who had been thinking about going to Africa as a missionary through the Church Missionary Society. But after several, heart-to-heart talks and prayer, Cassels’ interests shifted to China.

By September of 1884, God had opened Cassels’ heart for China and he also applied to go to China as a missionary through the C.I.M. The applications of Smith, Hoste and Cassels were accepted. After a brief farewell tour to awaken university students to the needs of China, the three were to leave for China by December of 1884. But God was not yet finished. God had a different plan.

Studd had been struggling about what God wanted to do with his life. He only knew that he wanted to devote his life in bringing Jesus to lost souls. Studd said, “I have tasted most of the pleasures that the world can give. I do not suppose there was one that I had not experienced; but I can tell you that these pleasures were as nothing compared to the joy that the saving of that one soul gave me.” Still, he became anxious about his future. Then God worked mightily in Charles’ heart once again and C.T. Studd, by faith, gave himself newly to Jesus. “I realized that my life was to be one of simple, childlike faith…. I was to trust in Him that He was my loving Father and that He would guide me and keep me, and moreover that He was well able to do it.”

Stanley Smith and Charles Studd had been friends for quite some time. In November of 1884, Smith invited Studd to a meeting at the C.I.M headquarters where John McCarthy, a returning missionary from China, would be speaking. Studd accepted the invitation and when McCarthy spoke of “thousands of [Chinese] souls perishing everyday and night without even knowledge of the Lord Jesus,” C.T. Studd was convinced that God was calling him to China. At first, he was hesitant because of his widowed mother. Even his older brother, a faithful Christian, tried to persuade him not to go. C.T. prayed and prayed until God gave him one word, “…a man’s enemies are the men of his own house.” (Micah 7:6) Charles Thomas Studd was going to China as a missionary.

Stanley Smith rejoiced at Studd’s decision. Studd’s decision also had a remarkable effect on Monty Beauchamp. Beauchamp had introduced the C.I.M to Smith, Hoste and Arthur Polhill-Turner but he himself had no desire to go to China. Studd’s decision to go to China influenced Beauchamp to reconsider. Beauchamp had a serious talk with Stanley Smith and he also met and spoke with Studd. On Nov. 4, 1884, Beauchamp studied his Bible and prayed for God’s leading. Afterwards, he was convinced that not only should he go to China as a missionary, he should induce others to do the same.

Meanwhile, Stanley Smith’s farewell tour was continuing and the departure date for China was postponed because of Studd’s decision. A week long mission was scheduled at Cambridge and Smith, Studd, Beauchamp, Cassels and Hoste were speakers and Hudson Taylor was also there. The Cambridge students were greatly moved because these five were not simply missionaries, but their own friends and classmates, people whom everyone knew and respected, especially C.T. Studd. On the last day of the mission, students who had decided that they would also go out as missionaries were asked to come forward and pray. Arthur Polhill-Turner was one of them.

Arthur Polhill-Turner had long been thinking about China but was not one to make rash decisions. Instead, he waited on God. He had several long talks with Studd and Smith and received much grace. Arthur also prayed and prayed until the Holy Spirit worked in his heart and convinced him that he was to join his friends in going to China as a missionary.

Cecil Polhill-Turner was still in the military but God had been working in his heart as well. Cecil had encouraged Studd to go to China but Cecil also had a personal calling from God. He went to a China missionary meeting, independent of his brother Arthur, and then personally visited Hudson Taylor in London for advice. Hudson Taylor said to him, “Let us have some prayer about it.” By January of 1885, both Polhill-Turner brothers were conscious of God’s pulling them to go to China. Together, they went to Hudson Taylor in London and “offered [themselves] for China.” Hudson Taylor accepted them as missionaries, believing that it was surely God’s providence to raise the number to seven. The seven were then scheduled to leave in early Feb. 1885. The seven continued the farewell tour and someone dubbed them “The Cambridge Seven.” The name stuck. God had forged together “The Cambridge Seven:”

For the next month, these seven young men toured the campuses of England and Scotland, holding meetings for the students. God used these students to bring revival throughout Great Britain. Everywhere they went, the meeting place was always filled with people. Many people, hundreds, even a thousand were converted each night through the simple but heart-moving testimony messages, which told simply the grace of God in their lives and why they were going to China.

Those who were converted at these meetings, went out and witnessed to their friends and brought them to Christ. Every night, it was the same messages and with the exception of Smith, none were talented speakers, but people kept coming and coming. The Queen of England was pleased to receive a booklet containing “The Cambridge Seven” testimonies. God had used “The Cambridge Seven” to shake the foundations of a sleeping church in England and awaken her newly to the Gospel of Salvation and World Mission.

The influence of “The Cambridge Seven” even came across the Atlantic to the United States and led to the formation of Robert Wilder’s Student Volunteer Movement, an organization which toured college campuses, encouraging students to volunteer as missionaries. Fittingly enough, the last farewell meeting was held at Exeter Hall and ended with an address from C.T. Studd:

“Are you living for the day or are you living for life eternal? Are you going to care for the opinion of men here, or for the opinion of God? The opinion of men won’t avail us much when we get before the judgment throne. But the opinion of God will. Had we not, then, better take His word and implicitly obey it?”

Third, Go ye into all the world and preach the gospel to every creature.

“The Cambridge Seven” obeyed the great commission command and after six weeks, arrived in Shanghai on March 18, 1885.

William Cassels worked hard in the mission field to bring souls to Christ. After ten years, he returned to England in 1895 where he was consecrated as the new Bishop of a new diocese in Western China. He returned to his mission field, Western China and brought the Gospel of Jesus to dying souls. He lived in Western China until his death 1925.

Stanley Smith was sent to North China. God enabled him to master the Chinese language until he became as fluent a preacher in Chinese as he was in English. His life in China was very difficult but he worked hard until the end, preaching and teaching until he also died in China on January 31, 1931. [He had been forced to resign from C.I.M. after 20 years over a doctrinal teaching].

C.T. Studd, the best known of “The Cambridge Seven,” was sent home because of ill health in 1894. But God recovered his health and he spent six years in India as a missionary and a brief period in Britain and America. Then, in 1910, he set off for the greatest challenge of his life, to pioneer the tropics of Africa. He had a strong, absolute attitude before God’s word and some people did not like him. He had to endure poverty and much suffering for the sake of evangelizing the native African people. But he loved Jesus and the native African people and labored to the end, as a Bible teacher and shepherd. When he died in the Belgium Congo in 1931, over one thousand native Africans saw him to his grave.

Arthur Polhill-Turner was a faithful Gospel worker. He was ordained as a minister in 1888 and moved to the densely populated countryside to reach as many people as he could with the Gospel message. He was in China throughout the uprisings against foreigners at the turn of the century and did not leave until 1928, when he retired and returned to England. He died in 1935.

Cecil Polhill-Turner, stayed in the same province with the others for awhile before moving steadily northwest, in the direction of Tibet. During a violent riot, Polhill-Turner and his wife were nearly killed in 1892 but after God restored his health, he returned to the border near Tibet to bring the Gospel to the lost souls there. In 1900, his health failed again, he was sent home to England and he was forbidden to return to China. But his heart was still in China and throughout the rest of his life, he made seven prolonged missionary visits. He died in England in 1938.

Montague Beauchamp loved the hard evangelistic journeys. Once, accompanied by Hudson Taylor, he went “about a thousand miles in intense heat, walking through market towns and villages, living in Chinese inns and preaching the gospel to crowds day by day.” He also co-worked with Cassels and was a source of blessing to the native Chinese people. In 1900, he was evacuated because of the uprisings but returned again to China in 1902. He returned to England in 1911 and served as a chaplain with the British Army. His son became a second-generation missionary in China and in 1935, although he was much older than his Cambridge days, he went back to China as physically strong and untiring as ever. He died at his son’s mission station in 1939.

Dixon Hoste lived the longest of “The Cambridge Seven.” Hoste was a faithful man of prayer and in 1903, he succeeded Hudson Taylor as the Director of the China Inland Mission. For thirty years, he led the Mission, which made great advances, reaching many with the Gospel until he retired in 1935. But he remained in China until 1945, when he was interned by the Japanese. He died in London, in May 1946, the last of “The Cambridge Seven” to die.

“The Cambridge Seven” revealed God’s power through their lives of fellowship, lives of prayer, and lives of devotion to their first love Jesus Christ. Their beautiful lives were a blessing to the whole world. May God raise up men such as these from the campuses of America in our generation.

Used with permission of Anthony B. Wong

You can use PayPal to make a donation or send a check in the mail. One time donations help temporarily but we need friends who will commit to giving regularly. Would you prayerfully consider doing so?

You can contact us if you have a prayer request or if you have any questions.